This is the first post in the series "Beyond the CLI". Check out the link to find out more.

The Problem You Already Have

As network engineers, we've all been there. It's 2am, something's broken, and you're staring at configuration wondering what's changed. Maybe you've got a folder somewhere with files named core-sw01_backup_2025_working.txt, you open it up in Notepad++, square-eyed trying to find the difference. Maybe you just don't know what it looked like last Tuesday.

This isn't a tooling problem you haven't solved, it's a problem you've been solving badly for years.

- Naming conventions

- Dated folders

- Email threads with attachments

- "Just SSH in and check the running config"

These all work, until they don't.

Git exists because software developers hit this same wall decades ago. They needed to track changes, collaborate without overwriting each other's work, and roll back when things went wrong. Sound somewhat familiar?

What Git Actually Is

Git is a Version Control System (VCS). At its core, it tracks changes to files over time and lets you move between different versions of those files. That's it. Everything else, such as branches, merges, pull requests, all build on that foundation.

Think of it like this: instead of saving config_v1.txt, config_v2.txt, config_v3.txt, you have one file called config.txt and Git remembers every version that ever existed. You can see exactly what changed between any two versions, who changed it, when, and why (if they bothered to write a decent commit message).

Git is also distributed, meaning every person who works with the repository has a complete copy of the entire history. There's no single server that, if it dies, takes your history with it.

Why Network Engineers Should Care

As a network engineer, you may think: "I'm not a developer. I push configs to devices, I don't write applications." It's a fair point. But consider what you actually do day-to-day:

You make changes that need to be tracked. Whether it's a routing policy update, an ACL modification, or a new VLAN, changes happen constantly. When something breaks, the first questions are always "what changed and is anyone doing anything?".

You work with text files. Device configs are simply text. Ansible playbooks are text. Terraform files are text. Python scripts are text. Git was built for exactly this.

You collaborate with others. Even if you're the only network engineer, you probably work with security teams, developers, or other infrastructure engineers. Git provides a common language and workflow for collaboration.

You need to prove what happened. Compliance, audits, change management, all of these benefit from an immutable record of who changed what and when. Git provides this automatically.

You want to automate. The moment you start building automation, whether it's a simple Python scripts or full CI/CD pipelines, version control stops being optional. You can't reliably automate config deployment if you don't have a reliable source of truth for those configs.

Key Concepts (Without the fluff)

Let's establish the basics. These terms will come up constantly, so it's worth understanding them properly.

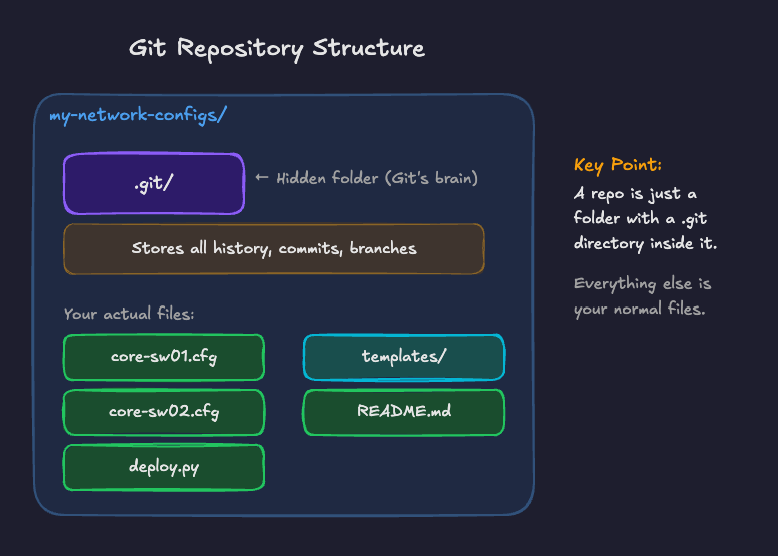

Repository

A repository (repo) is just a folder that Git is tracking. Inside that folder, there's a hidden .git directory where Git stores all the history and metadata. Everything else is your actual files; configs, scripts, documentation, whatever you're working with.

You could have one repo for your entire network automation project, or separate repos for different purposes. There's no wrong or right answer, but a common starting point is one repo per project or team.

Commit

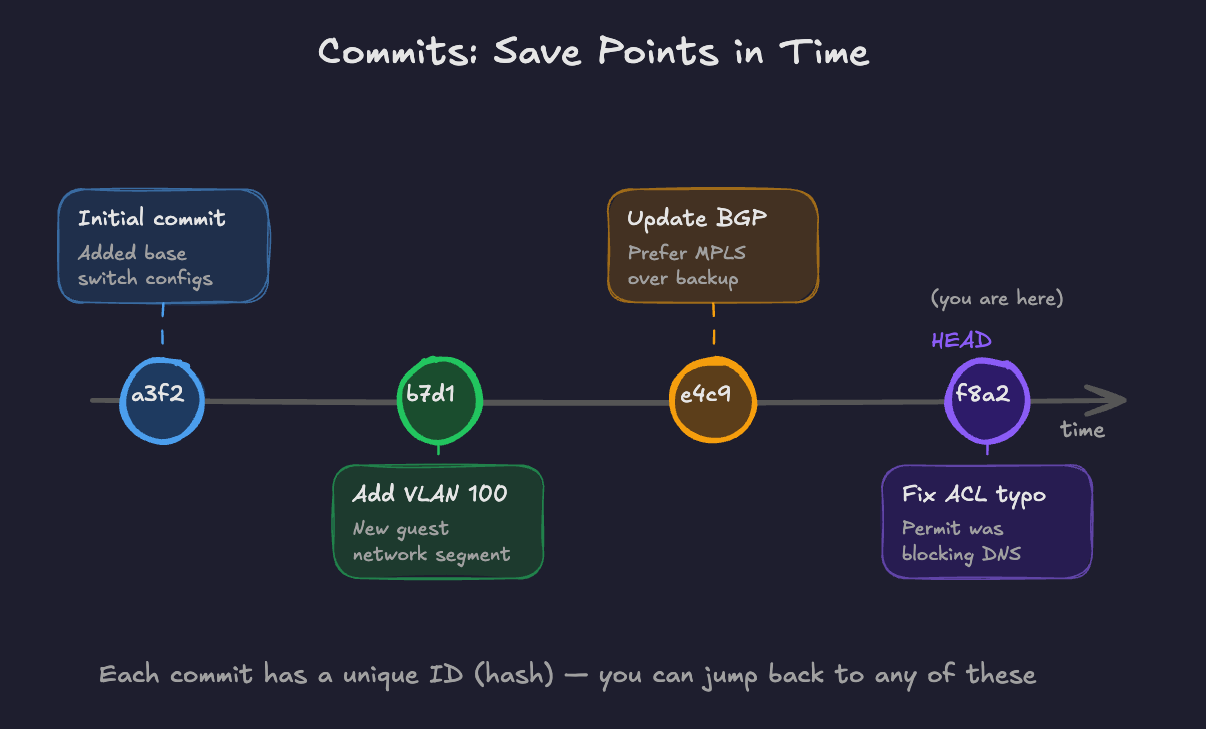

A commit is a snapshot of your files at a specific point in time. When you make changes and commit them, Git records exactly what changed, when, and includes a message you write describing the change.

Think of commits like save points. You can always go back to any previous save point. The difference is that Git keeps all of them, forever.

Good commit messages matter. "Fixed stuff" tells you nothing six months later. "Updated BGP policy to prefer MPLS path over internet backup" tells you exactly what happened and why.

Example command;

git commit -m "config pull 19th Feb 2026"

# commit command with message (-m)Branch

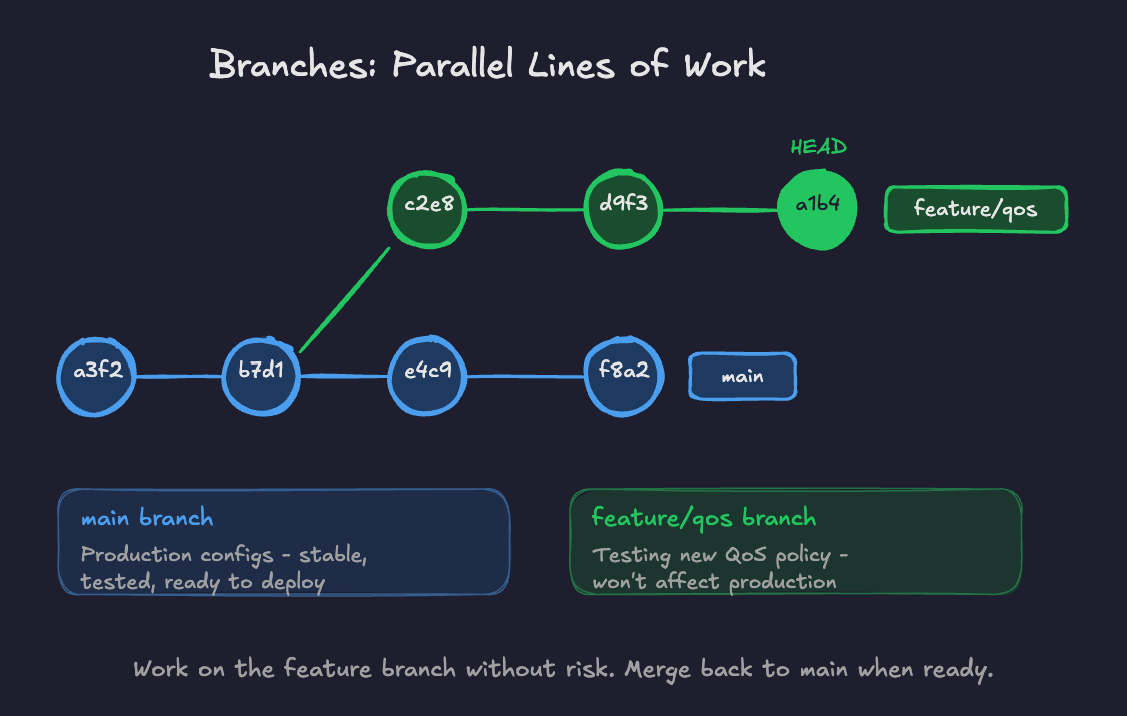

A branch is an independent line of development. By default, you have one branch called main (historically called master). When you create a new branch, you're essentially saying "I want to try or develop something without affecting the main version."

For network engineers, think of it like this: you want to test a new QoS policy. Instead of modifying your production configs directly, you create a branch, make your changes there, test them, and only merge back to main when you're confident it works.

Example commands;

git branch

# list all local branches

git branch -a

# list all local and remote branches

git branch <name>

# Create a new branch

git checkout <branch>

# Switch to branch

git switch <branch>

# Modern way to switch branches

git switch -c <branch>

# Modern way to create and switch branch.Merge

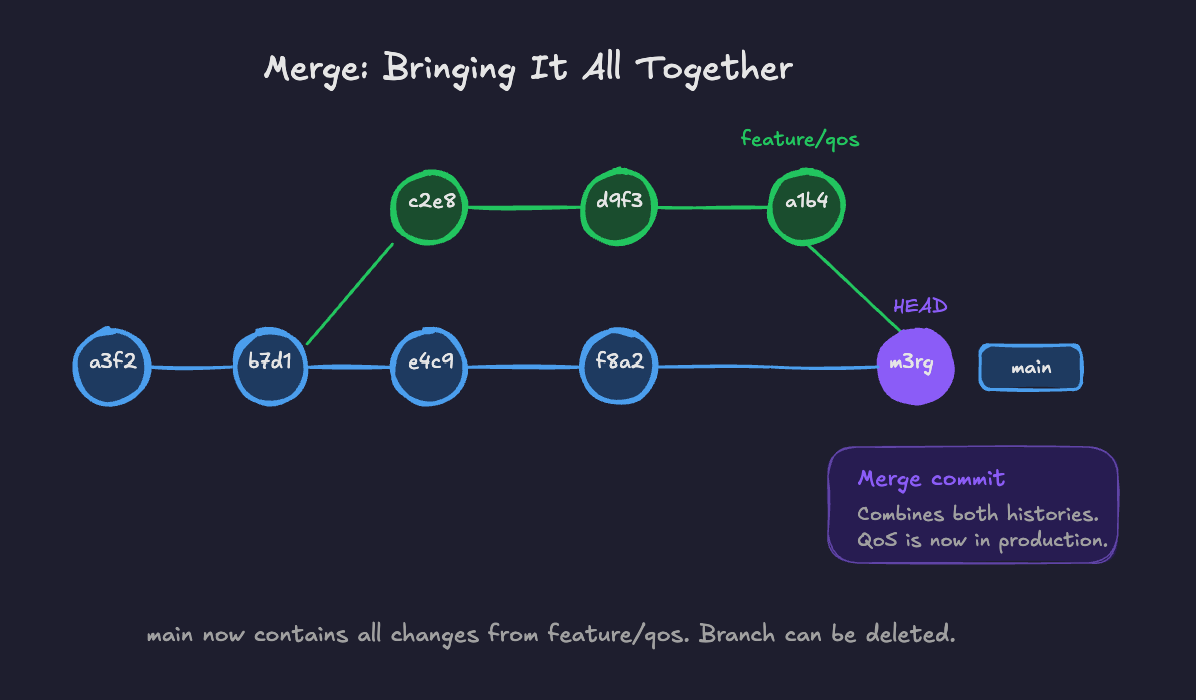

Merging takes changes from one branch and merrges them into another. If you've been working on a feature branch and you're happy with the changes, you merge that branch back into main.

Most of the time, it just works. Git is smart about combining changes. Occasionally, two people modify the same lines of the same file, and Git needs you to manually resolve the conflict. This sounds scary but is usually straightforward in practice. We'll run through this in the practical examples/ demo.

Example command;

git merge <name>

# Merges specified branch into current.

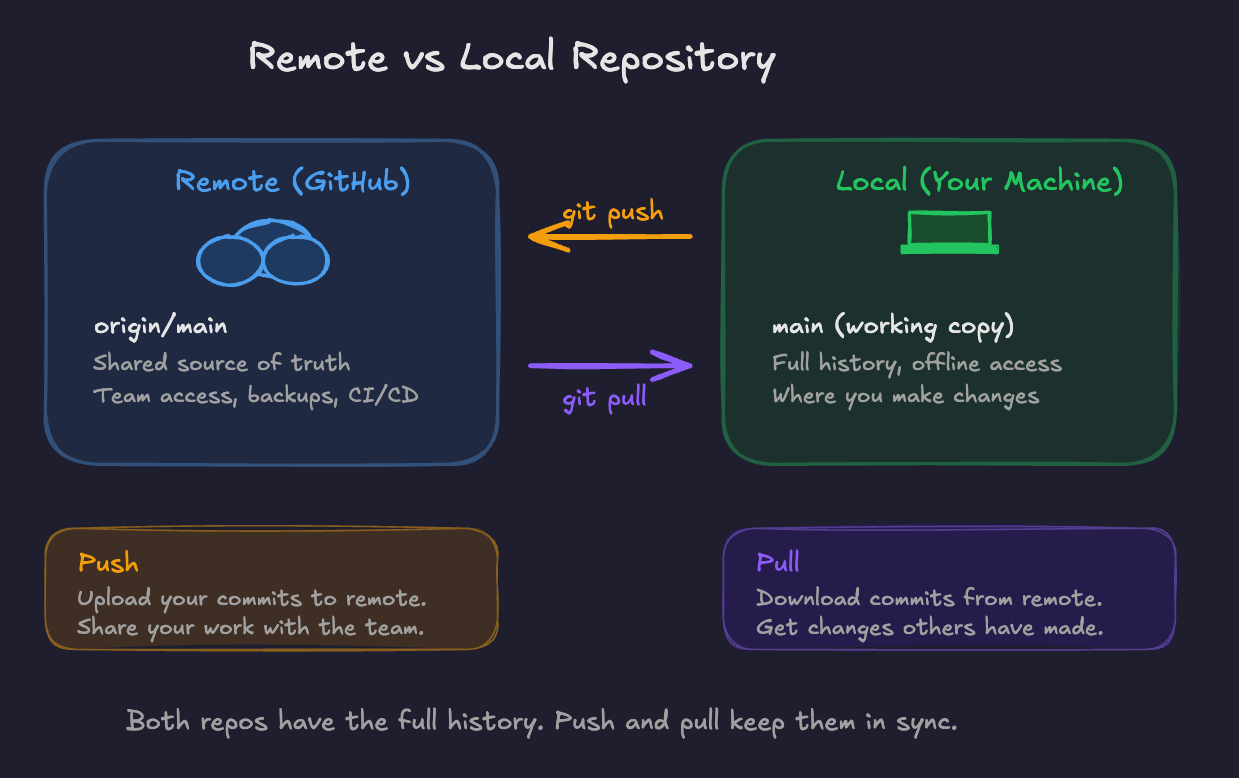

Remote

A remote is a copy of your repository hosted somewhere else, typically a service like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. You push your local commits to the remote to back them up and share them with others. You pull from the remote to get changes others have made.

This is where collaboration happens. The remote becomes the shared source of truth that everyone syncs with.

Git vs. GitHub (They're Not the Same Thing)

This trips people up constantly when starting with Git. Git is the version control system, the actual tool that tracks changes. It's free, open source, and runs locally on your machine.

GitHub, GitLab, and Bitbucket are hosting services that provide a place to store Git repositories along with additional features: web interfaces, issue tracking, pull requests, CI/CD pipelines (GitHub Actions in GitHub for example), access control, and more.

You can use Git without ever touching GitHub. You can have a Git repo that only exists on your laptop. But in practice, most people use a hosting service because the collaboration features are valuable and it provides an off-machine backup.

For this series, we'll use GitHub because it's the most common, has a generous free tier, and integrates well with everything else we'll cover. The Git fundamentals apply regardless of which hosting service you choose.

Join our new Discord community where we discuss everything; infra, cloud, AI and much more. Come vent, discuss tech problems, or just have a place to hang out with like-minded individuals.

How This Relates to Network Automation

Let's build on what we know so far with some network-specific scenarios.

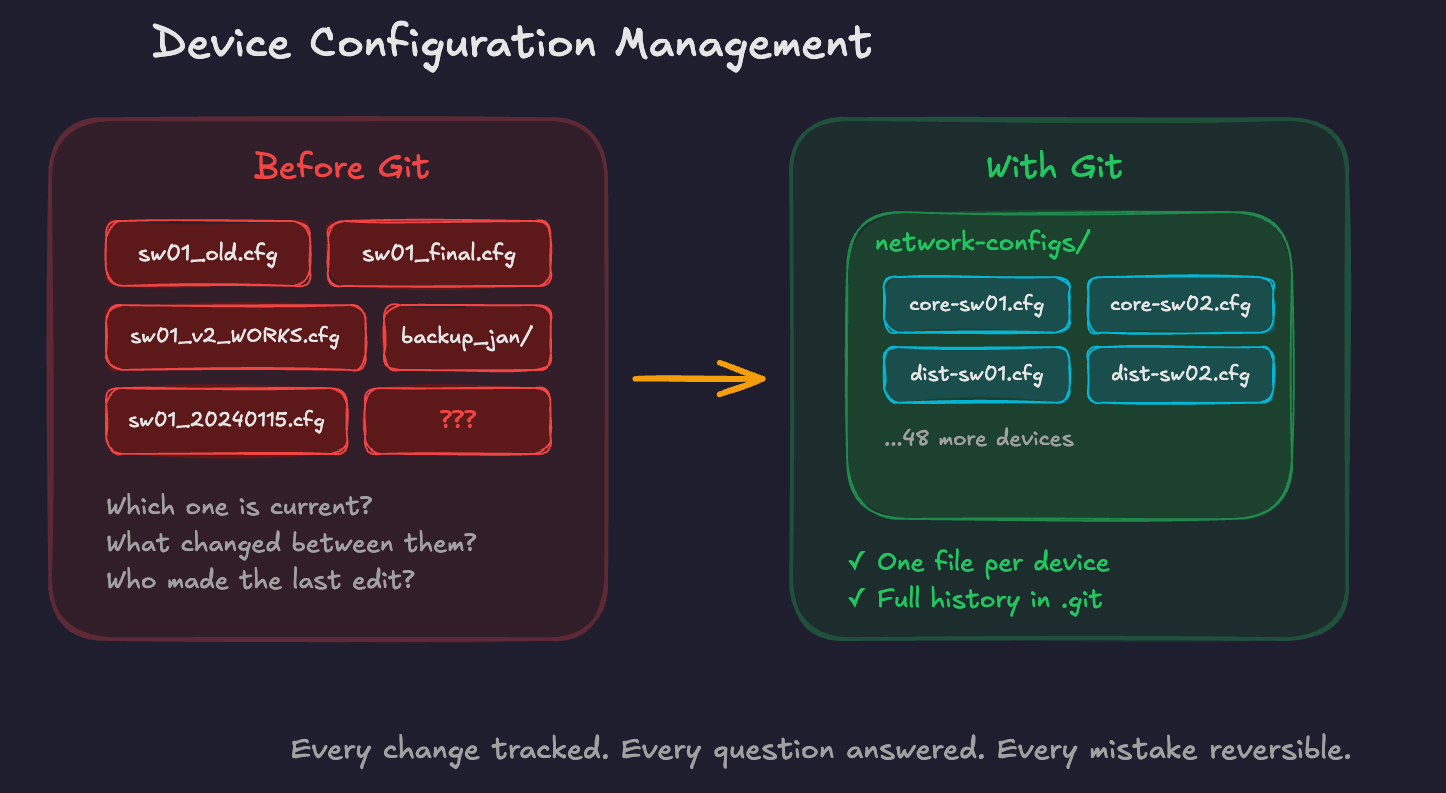

Scenario 1: Device Configuration Management

You're managing configs for 50 odd switches. Today, each device's config lives... somewhere. Maybe on the device itself. Maybe in a backup folder. Maybe in your head.

With Git, you have a repo containing a config file for each device. When you change a config, you commit the change with a message explaining why. When someone asks "what changed on core-sw01 last month?", you can answer in seconds. When a change breaks something, you can see exactly what was modified and revert it.

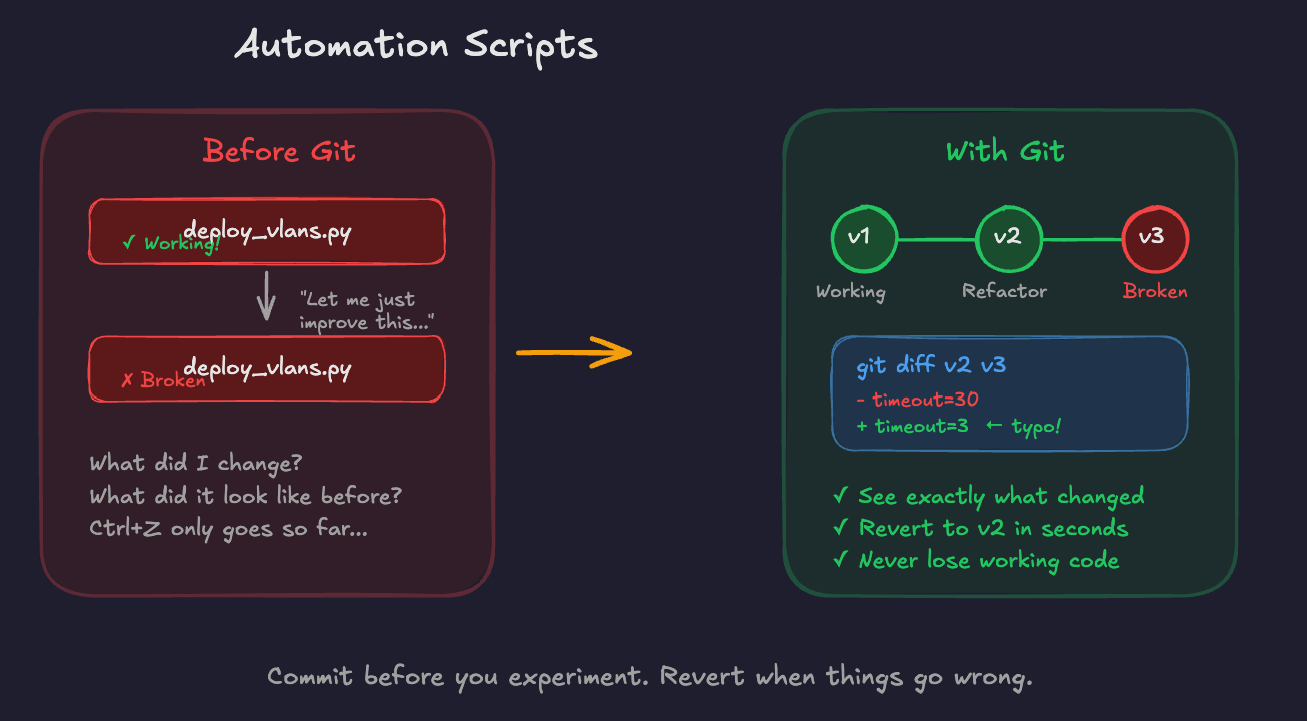

Scenario 2: Automation Scripts

You're writing Python scripts to automate routine tasks. You get something working, then try to improve it, and somehow break it. Without version control, you're manually saving copies (if any) or trying to remember what the working version looked like.

With Git, you commit the working version before making changes. If your improvements break things, you can see exactly what you changed or simply revert to the previous commit.

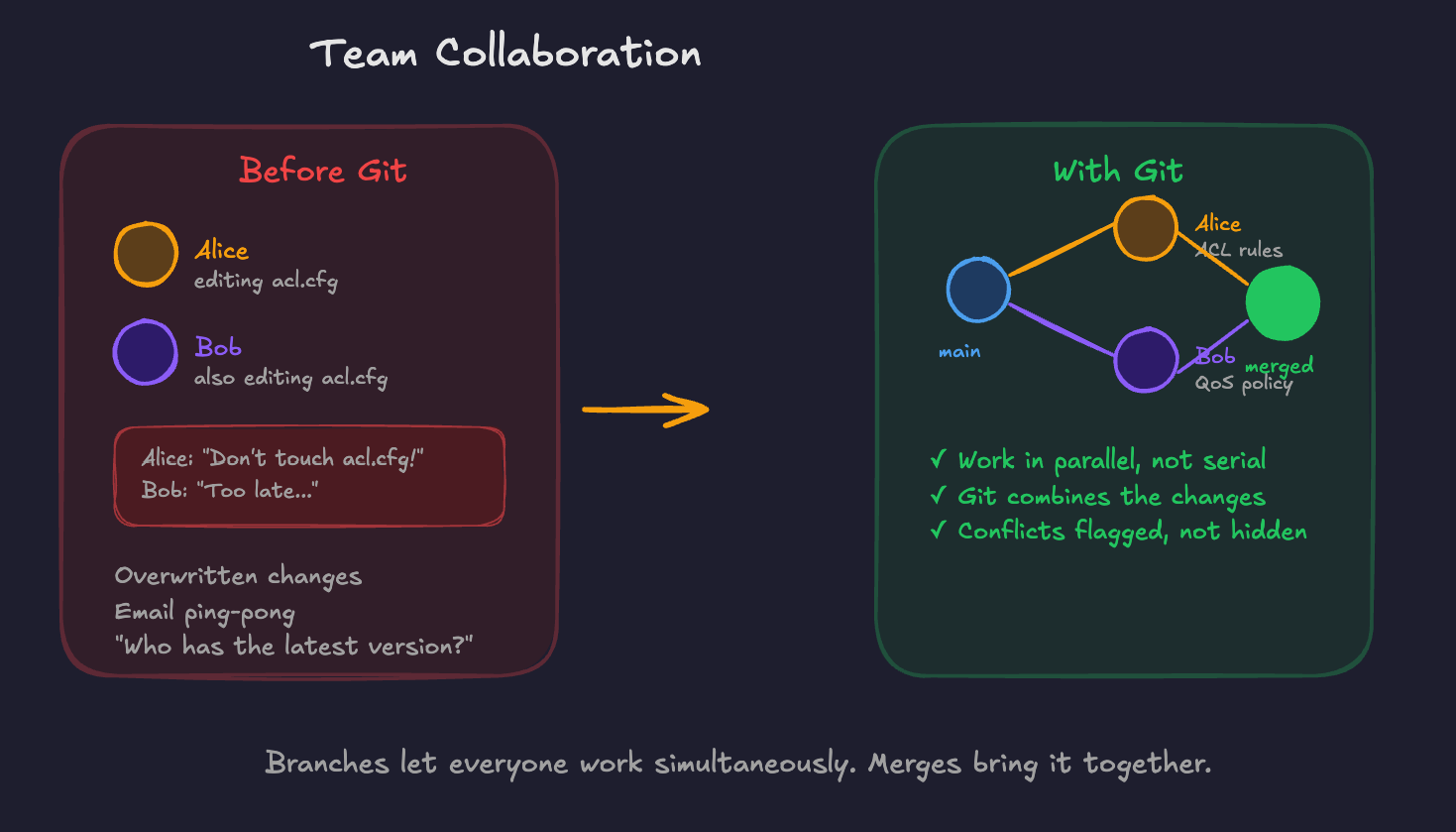

Scenario 3: Team Collaboration

Two engineers need to work on different parts of the network automation project simultaneously. Without version control, you're coordinating via Slack/ Teams, emailing files back and forth, and hoping nobody overwrites anyone else's work.

With Git, each engineer works on their own branch. When they're done, they merge their changes. Git handles the combination and flags any conflicts that need manual resolution.

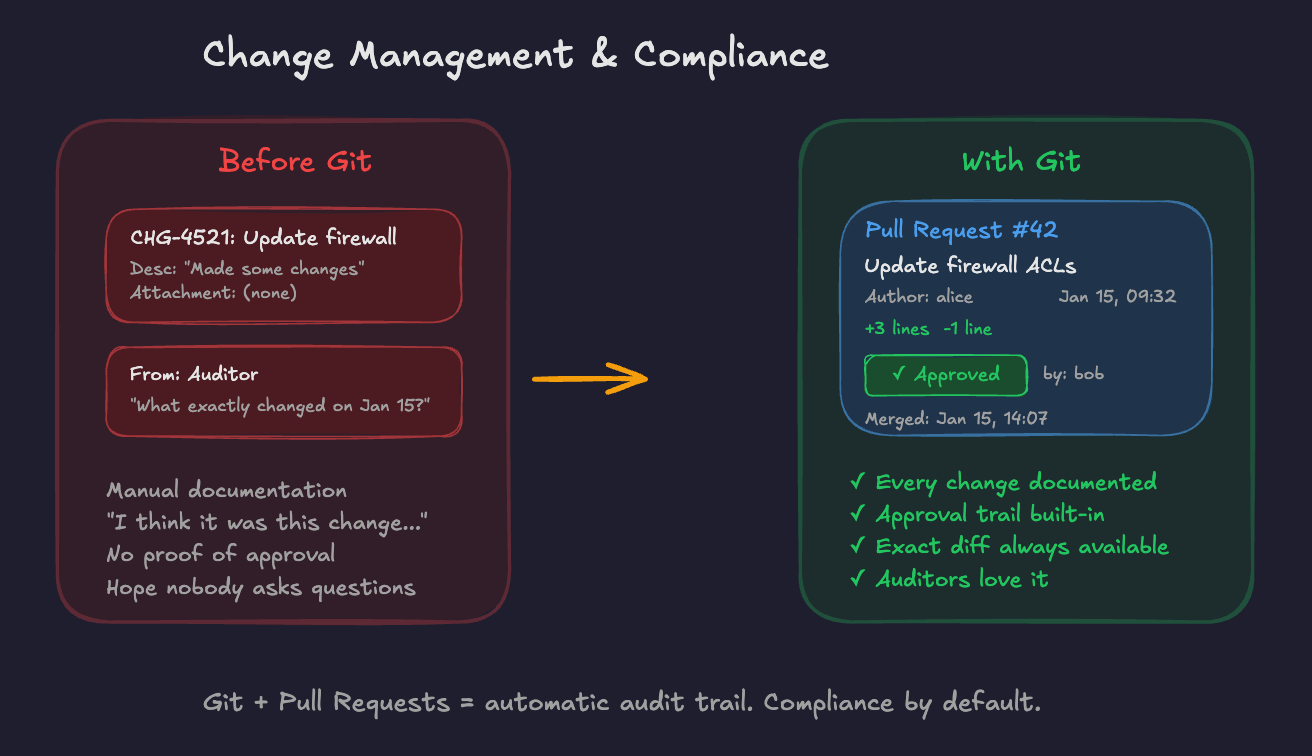

Scenario 4: Change Management and Compliance

Your organisation requires documentation of all changes, approvals before deployment, and audit trails. Currently this involves tickets, manual documentation, and hoping everyone follows the same process to a tee.

With Git (especially combined with a platform like GitHub), changes are proposed via pull requests, which can require approvals before merging. Every change is automatically timestamped and attributed to a user. The complete history is preserved indefinitely.

The Mindset Shift

Adopting Git isn't just learning new commands. It's changing how you think about configuration and automation work.

Think in changes, not states. Instead of "here's my config," start thinking "here's what I changed and why". This shift makes troubleshooting easier and produces better documentation as a side effect.

Commit early, commit often. Small, focused commits are easier to understand, review, and revert than massive commits that change fifty things at once. Get something working? Commit it. About to try something risky? Commit first.

Write for your future self. That commit message isn't for Git, it's for you, six months from now, trying to understand why this change was made. Be kind to future you.

The repo is the source of truth. Once you adopt Git, the repo should be authoritative. The config on the device should match the repo, not the other way around. Drift happens, but the goal is to minimise it and reconcile regularly.

What's Next

In this post, we covered the why of version control and the key concepts you'll need going forward. We haven't touched a terminal yet, and that's intentional. Understanding what Git is trying to accomplish matters more than memorising commands.

In the next article, we'll get practical. You'll set up Git, create a repository, make commits, work with branches, and connect to GitHub. We'll do this in the context of network configs so the examples are immediately relevant to you.

By the end of this series, Git will be the foundation everything else builds on: your Terraform configs will live in Git, your CI/CD pipelines will trigger from Git, and your automation code will be versioned in Git. It all starts here.

Part 2: Git in Practice